After four decades working for the Queensland Museum, Gary Cranitch is still immersing himself in dauntingly large, timelessly important new projects.

Aerial, Australian Pelicans over Lake Galilee, Central Queensland.

This year is your 40th working for the Queensland Museum. How did you start out in the job?

I took up photography at the age of 11, with a home darkroom in the laundry. I went on to get an associate diploma of photography and I started at the Queensland Museum at 21 as a photography assistant. I spent four or five years processing film ad nauseam and making black-and-white prints in the darkroom, then a few people left and I moved up to actually taking photos. Now I’m probably the longest-serving photographer in the state government and I must be close to the longest-serving employee at the museum.

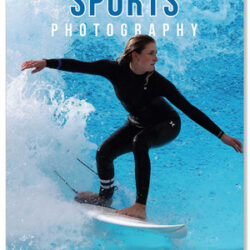

Being a photographer for a major public museum seems like a rare specialisation – or is it more about having to cover a lot of bases?

I call myself a natural history, landscape and cultural heritage photographer, and my knowledge has constantly increased in that space. The museum’s a very public-facing organisation, with a number of campuses around the state, and photography is front and centre in terms of both exhibitions and publishing for telling the historical and cultural stories of Queensland. That’s how my role has continued to be important and relevant to the organisation, whereas other government departments have ditched their photography because they no longer want or need it.

We all have parts of our jobs that aren’t our favourites, but increasingly my skill has been directed towards natural history and wildlife because that’s my strength. And those sorts of images are timeless and hugely important for recording what’s going on on the planet. Certainly, for the last 20 years, that’s where I’ve spent the bulk of my time. Chasing wildlife, hanging out of aeroplanes, getting underwater.

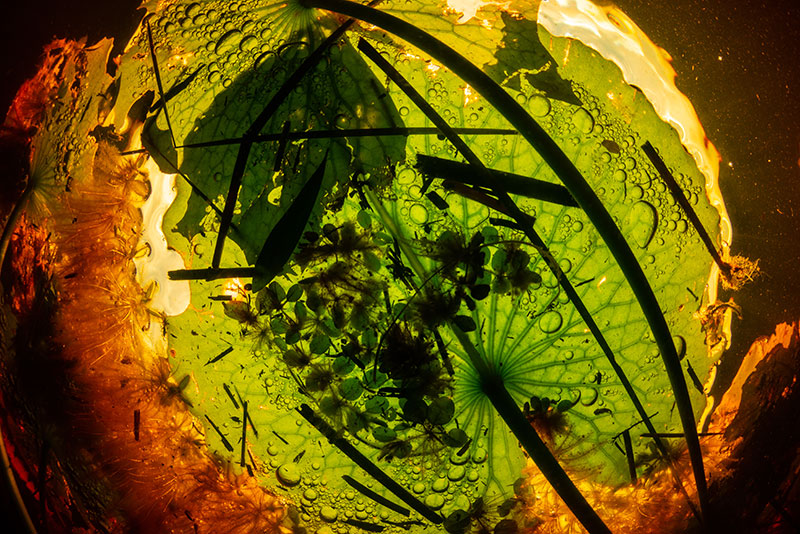

Underwater image in freshwater wetland Minjerribah (Nth Stradbroke Island).

Coral spawning on the Great Barrier Reef, Vlassoff Reef off Cairns.

So you do underwater photography as well?

Working on shipwrecks in the 1990s started me off, and in 2000 I completed a five-year project to produce a big book on the Great Barrier Reef. That book is similar to one I’ve just done on wetlands (Wetlands of Queensland: A Queensland Museum Discovery Guide, published in September 2013), for which I shot 22,000 images, with about 700 going into the book. But it’s all there forever in our digital asset management system, where metadata is king.

In that respect, I also function as the photo editor. We have image librarians who look after the IT support, but I do the data crunching and extended captioning, be that GPS locations, names of animals, genus, species, and all that sort of stuff. That’s the non-romantic side of this job.

These sorts of projects are enormous challenges, and while I’m very self-motivated to get them done, collaboration is hugely important. It involves different groups and people all over the state who really know their stuff. For example, with the wetlands book, there was the Department of Environment and Science, and for the reef book, the Great Barrier Reef Foundation. Also universities and many other organisations.

When you’re out taking photos, do you work alone?

Pretty much. I do most of the planning and organising of where I’m going to go, how I’m getting in, getting the shots, and getting back again. I try to limit periods away from home to around a week to 10 days because, after that, I start to fatigue.

The museum must provide you with an extensive range of photographic equipment.

Actually, I run a pretty lean kit. Two Nikon D850 cameras with a 300mm f/2.8 and 70-200mm, 16-35mm, 24-70mm, and 14-24mm zooms, plus 60 and 105mm macros. For the underwater housing kit, it’s a D800 with an 8-15mm in a Nauticam housing. I have flash units (strobes), but almost everything I do is available-light.

Aerial, tidal mudflats, Princess Charlotte Bay, North Queensland.

Aerial, Lake Mipia near Bedourie western Queensland.

With Queensland being such a varied, spectacular part of the world, you must never be short of subjects.

It’s incredible, amazing. The biodiversity, the landscapes, and habitats. In one day, you can fly east to west and go from coral reefs to mangroves to rainforest to eucalypt forest and finish up in the desert. Of course, it’s huge too. Just some of the work I’ve done in the last couple of weeks – aerial work in the Gulf of Carpentaria and the Wet Tropics, documenting the unprecedented big wet season they’ve had up there – has emphasised how vast and isolated so much of Australia is.

I’ve also started work on a new book on K’gari (Fraser) Island, working closely with the traditional owners, the Butchella people, to help me see it through their eyes, which is a fabulous experience.

Having photographed many of these places several times over the years, what’s your perspective on the effects of climate change?

As an example, put it this way. I kicked off the wetlands project in 2019, the driest year on record in Australia at the end of seven to nine years of drought, when the country was a desolate dustbowl. A great time to start doing a book on wetlands, right? But the result was that I got this duality of what the country looked like when the water came back in 2020 and ’21. I’ve seen those sorts of extremes in other environments as well, such as periods of coral bleaching, crown-of-thorns starfish, and reefs being more frequently smashed by cyclones and the like. It’s a perfect storm of hit after hit after hit.

Aerial, farming land near Kingaroy, southern Queensland.

Aerial, farming land near Nanango, southern Queensland.

Aerial, cattle feeding lot, Millmerran, southern Queenland.

Aerial, cattle at drinking trough near Julia Creek, western Queenland.

How do you balance your documentary or scientific responsibilities with the aesthetic or artistic aspects of photography?

It’s a mix of art and science, and the two run well together – the responsibility to tell stories that are factually accurate, but have some emotion and feeling attached to them. I believe the best images usually have an emotional impact first, and all the other things come after that, be they technicalities or specifics.

Now that you’re nearing the end of your career, does it change the way you approach the work you do?

I’m not at the end of my career yet, but I know it’s coming, and it does make me think about my legacy. I’ve become more acutely aware that it’s important to pursue things that matter. It’s important to get those stories across to the many people in this country who rarely, if ever, leave a CBD. That includes mining, farming, small cropping… everything that makes this country what it is. You can’t just look at one part of the country and understand it, because it’s all connected. What happens on the land runs out into the sea, and all those sorts of things.

At the same time, I’m always looking forwards, to the next project. I feel I haven’t taken my best photographs yet.

Article by Steve Packer

Excerpt from Photo Review Issue 97